During the first weeks of the new administration, many Americans were desperately looking for a place to understand how to show up in this current moment. Whether or not you agreed with Executive Orders, it was difficult to keep up with the pace at which they were coming out. Each new day brought and continues to bring headlines that can feel like the world is fundamentally shifting. That amount of change can be exhausting. During that time, Eric Liu of Citizen University put out a call for 5 P’s to regain your footing: Patterns, Perspective, People, Place, and Power.

One of the Ps, Perspective, invites us to look at something that gives you perspective, “That can be historical perspective, which shows us in different ways that the United States has been here before and how citizens like you navigated then.”

I thought about perspective when I recently returned to the Sand Creek Massacre exhibit at History Colorado. The first time I visited, with the Civic Canopy team back in 2023, I had the opportunity to hear from Gail Ridgely, a Sand Creek Massacre descendant and enrolled member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, about the exhibit and the history it holds. Returning after the 2025 inauguration, my experience of the exhibit shifted in light of the current moment.

Told from the perspective of the massacres’ descendants, the exhibit recounts the story of the deadliest day in Colorado’s history:

At Sunrise on November 29, 1864, the US Army attached a peaceful camp of mostly women, children, and elders on Big Sand Creek in Southeastern Colorado. The Soldiers knew that the Cheyenne and Arapahoe were supposed to be under their protection. We were flying the US flag and the white flag of surrender. Colorado’s territorial governor told our people that these flags would demonstrate our peaceful intentions. But instead of protecting us, the soldiers murdered more than 230 of our people in the most brutal ways imaginable.

Once again, I was hit with grief as I took in this atrocity. The moment we’re in now and the moment that leaders faced leading up to the massacre are very different, but what links them is the need to make decisions when people’s rights and lives are at stake. What stuck out to me this time was the challenge of leadership in the face of unimaginable change. The exhibit says:

Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs made every effort to create a lasting peace with the United States. In a gesture of goodwill, they surrendered most of their weapons except for the ones they needed most for hunting. But by 1864, some Cheyenne and Arapahoe leaders wanted to fight. They thought that US would never keep its promises. They thought that resisting with military force was the only option.

But we also had leaders who wanted to keep trying for peace. In 1864, a respected Cheyenne leader, Black Kettle, sent a letter to Colorado’s territorial governor, John Evans, asking how to achieve peace. The governor was reluctant to meet but told Black Kettle to bring a peaceful delegation to Camp Weld, the military outpost in Denver.

Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders met Governor Evans and Colonel John Chivington. They told us that if we went to Big Sandy Creek and stayed there, we would be considered peaceful and would be protected by US troops. But Evans and Chivington betrayed us in the worst possible way.

One could look at this story and determine that the right type of leadership would have been to fight since they were betrayed and that seeking peace was a weak style of leadership. One could also argue that the truest form of leadership was to lead with integrity, in this case committing to the peaceful path at all costs. Even though the massacre took place, the exhibit still uplifts the leadership of those like Chief Black Kettle who worked for peace. Ultimately, I can’t weigh in on what was the right path. It’s something that only the Cheyenne and Arapaho can speak about.

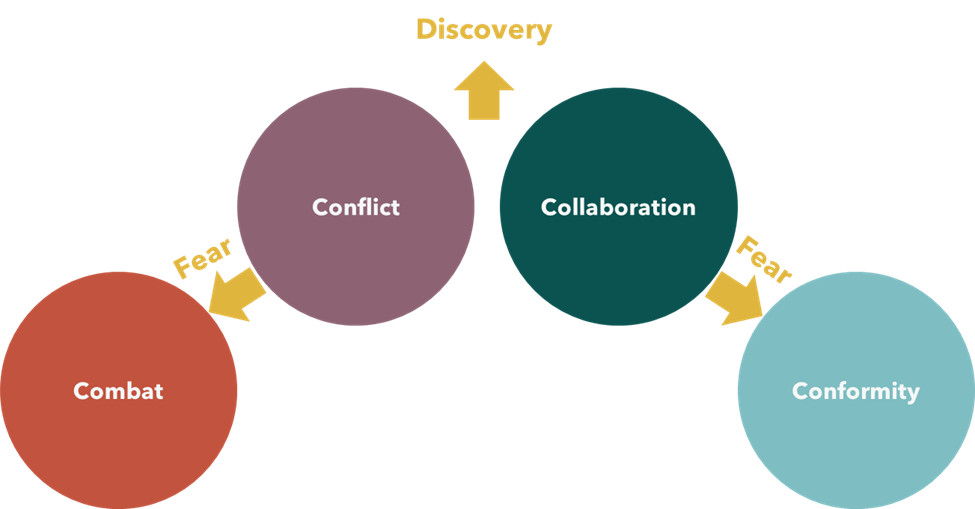

While most of us won’t face this kind of existential leadership threat, we do face a similar tension between conflict and collaboration all the time. Laurie L. Mulvey, Sheffy Minnick, and Michelle Frisby describe their interplay in Transforming Conflict and Collaboration. We can think of these two forces as interdependent, like two sides of the same coin or inhaling and exhaling. We need both. We can’t breathe without either. But we have to figure out how to get the best of both. Conflict is an encounter between alternative ways or contrasting perspectives. In the conflict camp, we see the energy of disagreement, diversity, and difference. It can protect us in the face of danger. Whereas collaboration is the force that brings people together and has the energy of unity, agreement, and commonality. It helps us create peace.

But they each have their shadow side when taken too far. We can think of these as only inhaling or only exhaling. Too much inhaling and we can’t release carbon dioxide. Too much exhaling and we don’t get enough oxygen. When we experience the disagreement of conflict and fear that we won’t get our needs met, we move into the violence of combat. We try to eliminate differences to make sure we get what we want. Alternatively, when we fear we won’t be able to arrive at a single conclusion or path forward in collaboration, our fear leads us to conformity. This is simply another way of eliminating differences, but in this case, we downplay our own perspective to go along to get along. We can get the best of both conflict and collaboration by leaning into discovery, which means getting curious instead of leaning into fear.

It’s easier said than done and I’ll admit that recently I froze when faced with this tension. I was standing in line at Best Buy, waiting to return a microwave, scrolling through my email and trying to find a receipt. The man behind me said, “1,000 watts that’s pretty good.” I told him I was returning it; he told me about the remote he was buying. As I turned back to try and find my receipt, he said, “Wanna hear a joke?’ He told me three jokes about something ridiculous Biden had recently done. When I didn’t respond the way he hoped, he asked if I had been disappointed in the results of the most recent election. With each question, I found myself trying more and more to just shift my body language, but he persisted. When I answered how I voted, he started to pepper me with questions about what I did or didn’t know about the candidate I voted for until I said, “Sir, I really don’t want to have this conversation in the line of Best Buy.”

There it was. I had shut down the conversation. I got nervous and I panicked. He told me this was the problem with sensitive liberals, we couldn’t have civil conversations anymore. I felt myself getting put in a box based on who I voted for when the reality is that I feel much more akin to the orientation Eric Liu described in a CNN interview, “I am a Democrat, but I am not a partisan for my party. I am a partisan for democracy.”

I waited through the awkward next seven minutes in line, quickly returned my microwave, and drove home. The whole while I was kicking myself for all the things I could have said instead:

- “I don’t think either of us can truly know the full story by just knowing who we voted for. Can you tell me more about your hopes for the country right now?”

- “I didn’t think either candidate represented all my interests. I’d love to know about an issue you ended up feeling conflicted about.”

- “I’d be happy to share what was important to me when I made my decision, but I’d like to share my perspective and hear yours, not debate. Would you be open to that?”

This was my job for goodness sake! Even with all my years of training, I know why I froze, because I know why so many people freeze. I saw a potential conflict and I got scared that it would turn into combat. I didn’t access my sense of discovery.

As we feel the potential stakes of getting it wrong increase, worrying about the physical safety of ourselves or the people around us, it gets harder and harder to access discovery. I haven’t gotten it right every time and I’ll mess up again. But after heeding Liu’s call for perspective, I find myself rooted in the commitment to try again.