If anyone knows how to get their hands dirty, it’s the folks at Pueblo Food Project (PFP). Whether they are growing food in untraditional places, helping new food entrepreneurs grow their own businesses, or feeding hundreds of people throughout the pandemic with a choice-centered food pantry, the Pueblo Food Project network is always ready to roll up their sleeves and take action. So, when the coalition went through a few bumpy transitions after several exhausting pandemic years, they looked to the Civic Canopy for support to move through a cycle of decay and renewal.

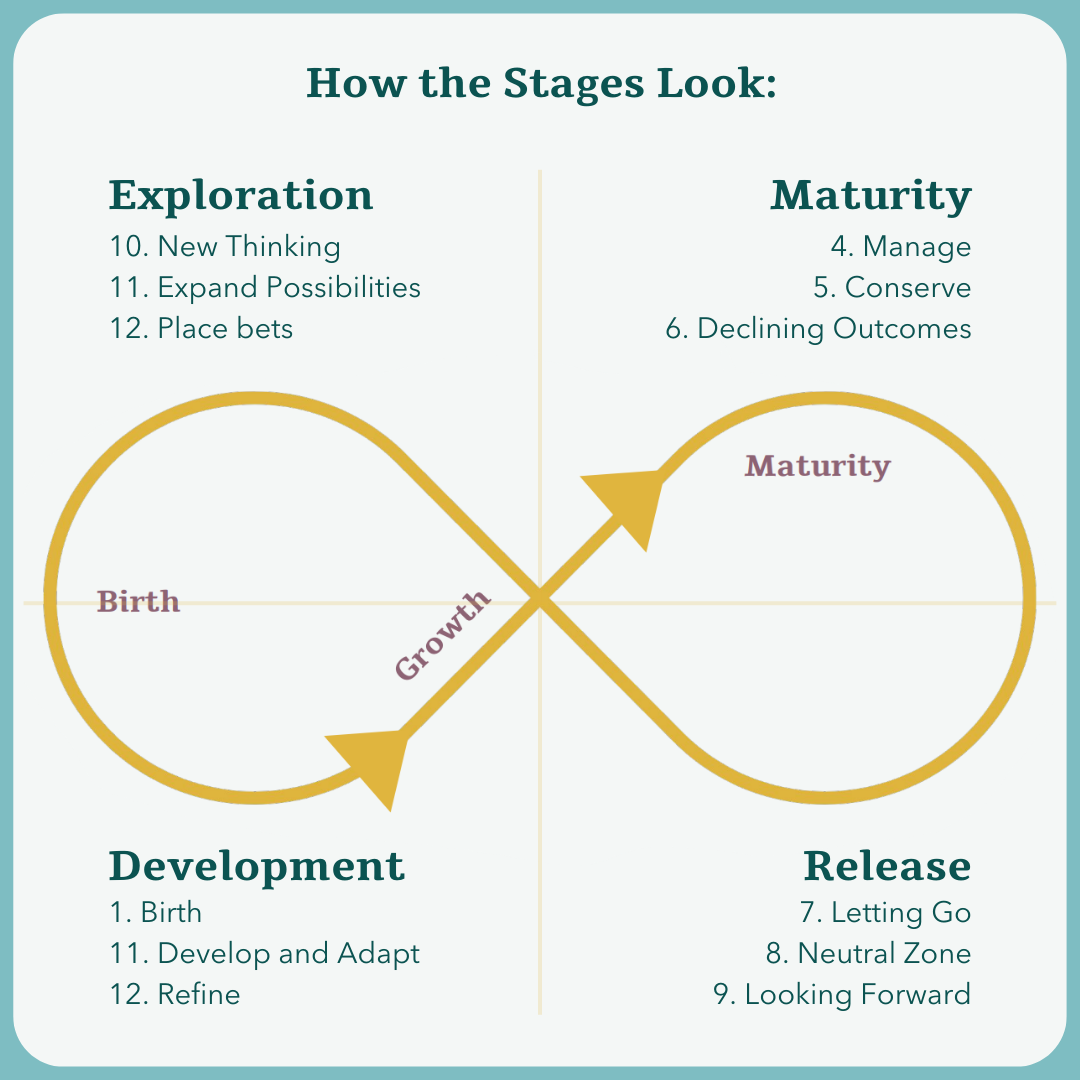

Like any group of people working together, coalitions are not a linear business. They go through cycles – moving through stages of birth, growth, maturity, release, and exploration. Along this process of decay and rebirth, there are plenty of traps that groups can fall into. One particularly sticky spot is the movement between the maturity stage and release – the rigidity trap. The rigidity trap looks like an inability or unwillingness to change, resistance to new ideas, or doing things the way ‘they’ve always been done.’ Letting go of the structures and stability that a group has built can leave coalition members feeling shaky, lost, confused, and often even grieving. It can feel like you may lose all that you’ve worked towards, and you may actually lose people (staff turnover, leadership change, loss of engagement, or loss of interest). Groups may question their very existence or wonder what they are truly there to do.

Like any group of people working together, coalitions are not a linear business. They go through cycles – moving through stages of birth, growth, maturity, release, and exploration. Along this process of decay and rebirth, there are plenty of traps that groups can fall into. One particularly sticky spot is the movement between the maturity stage and release – the rigidity trap. The rigidity trap looks like an inability or unwillingness to change, resistance to new ideas, or doing things the way ‘they’ve always been done.’ Letting go of the structures and stability that a group has built can leave coalition members feeling shaky, lost, confused, and often even grieving. It can feel like you may lose all that you’ve worked towards, and you may actually lose people (staff turnover, leadership change, loss of engagement, or loss of interest). Groups may question their very existence or wonder what they are truly there to do.

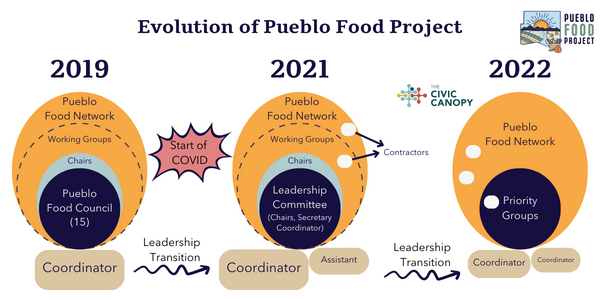

This was where the Pueblo Food Project found itself in the spring of 2022 when they started working with the Canopy team. A big shift in leadership along with uncertainty within the project’s home within the City of Pueblo left the foundation feeling shaky. The Pueblo Food Project began as a convening of 30 stakeholders brought together by U.S. Senator Michael Bennet’s Office and Walter Robb, former Whole Foods CEO, to focus on Pueblo food systems. With financial support from the Colorado Health Foundation’s Community Food Systems Planning Grant, PFP was able to develop a coalition as a project under the City of Pueblo. They were able to conduct a food access survey with over 1,160 respondents, conduct a market scan to determine what businesses need to grow a local food economy and develop a robust implementation plan structured around working groups. But two years later, after PFP responded to a food crisis exacerbated by the global COVID-19 pandemic, the Civic Canopy came into the picture. We were hearing that these detailed plans and structures had become a bit stale. The plethora of ideas that had been generated at the beginning of the group’s history were hanging out in documents, and slow progress was being made with varying degrees of success. So, the Canopy team started listening and discovering what may need to shift within the PFP coalition.

If PFP knows how to get their hands dirty, they also know the value of composting. The beauty of the release phase is that in letting go of the practices, structures, and processes that are no longer needed, a group can release the energy it took to uphold those systems and recycle it back into the soil to fuel whatever comes next. Just like compost, releasing can:

- Be pretty yucky (compost smells!)

- Take a long time

- Be filled with mystery, magic, and ambiguity

- Need more rest than action

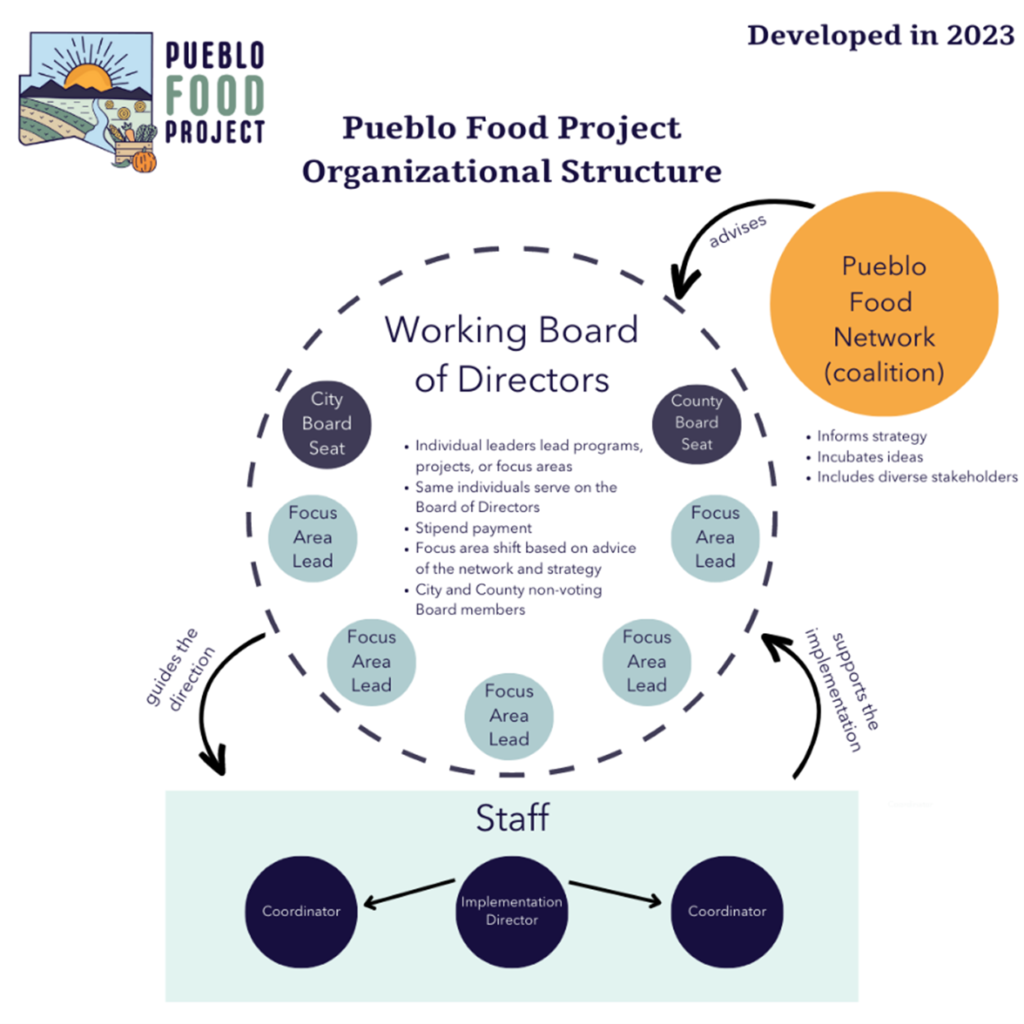

As the Pueblo Food Project turned the corner from release and started to move towards exploring a new version of the organization, there were a few key tools they used that allowed the new seeds to grow. PFP was determined to center the voices of community members. So, they chose to move away from traditional leadership structures and explore distributed leadership models. They also needed to decide on a legal and tax structure that would work for what they were hoping to become—would it be best to be a 501(c)3, a fiscally sponsored organization, or a business? They eventually settled on a new organizational chart that centers shared power and community leadership and decided to move towards a fiscal sponsorship that would help them eventually become their own 501(c)3 nonprofit. The PFP coalition working groups have always been run by dedicated volunteers as well as stakeholders involved through their professional work. During this transition, PFP focused on developing and nurturing their network of leaders within the coalition, providing opportunities to build skills, access training, and share in decision-making using consensus-building decision-making. The Civic Canopy provided support in group facilitation, guidance using the Community Learning Model, personalized leadership coaching, tools for coalition-building, conflict mediation, and group decision-making around the future organizational structure.

Now that the new version of the Pueblo Food Project is starting to sprout from the seed, the group is looking to what comes next. The next phase will include expanding the PFP network and listening deeply to the needs of the Pueblo community. They’ll revisit the huge amount of data and ideas that the group has already generated and take the pulse of what is still relevant. To create a more vibrant, nutritious, and equitable food system for every eater in Pueblo County, the Pueblo Food Project will need to engage more of the people, perspectives, and systems involved in the work. It’s a sort of full-circle, cyclical moment where the coalition finds itself in a similar, though more evolved, position than it was at its birth. To get here, they had to go through the stickiness of decay, composting the older version. It’s now time for new and improved ideas, creativity, and innovation—and PFP’s friends at the Civic Canopy will be eager to see what this next season brings.