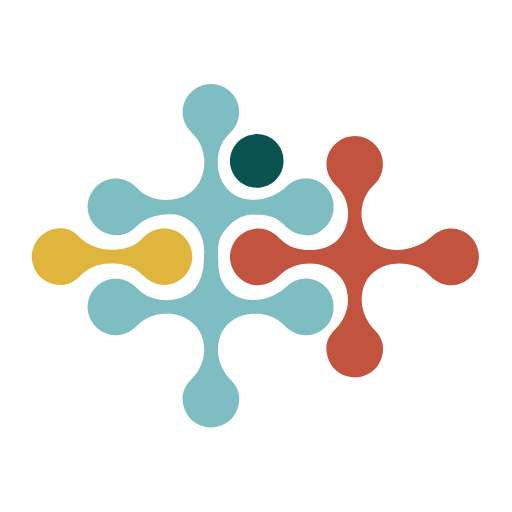

A new teammate at the Canopy recently asked me about the term we use “transferring capacity”—we even have a neat graphic to explain how we believe that our role is to enhance and elevate the capacity of the community who are ultimately the stewards of a project’s success. My teammate was wondering, what does transferring capacity look like? Do we come up with an idea and then pass it off to folks in the community? In my experience, the answer to that is, usually, no. It’s not nearly as neat as these triangles would suggest. Our part in a story is just that—a part of a whole. We are part of a whole history, a whole community, a whole interwoven tapestry; and the Canopy, a guest weaver, takes up a portion of that story whose threads will continue into the next frame.

So, I wanted to explore one of these instances of being a guest weaver, and how it unfolded from my point of view.

Most of my stories of work in the community start in a coffee shop. Unsurprisingly for folks in Pueblo, this one started at Solar Roast Coffee, where it’s nearly impossible not to run into three more people, which is where I first met Alexis Ellis. At the time, she was the Executive Director of Pueblo Triple Aim Corporation which has been serving as the backbone organization since 2019 for a joint city and county Community Commission on Housing and Homelessness working towards a vision where “every person in Pueblo has access and opportunity to suitable, safe, and affordable housing.”

Then there was a shift—a disruption. In December 2022, Pueblo Triple Aim Corporation (PTAC) decided to close its doors. This left the commission wondering how (or if) it would continue without the skilled facilitator who had coordinated these cross-sector meetings and supported work groups around education, data, zoning, resources, and rehabilitation. After some canceled meetings, the mayor’s office decided to host the next meeting in February and try to get the commission back on track. They decided that they would find a way to move the backbone support into the city by hiring a new position within the Housing & Citizen Services department whose work aligns with the commission. But that new employees wouldn’t be hired for at least a few more months…

When I heard that PTAC was dissolving, I attended the February commission meeting in hopes of seeing how this collaborative work around housing and homelessness could continue. When it was clear that there wasn’t a clear path for facilitation (outside of the very busy mayor’s Chief of Staff), I offered to support in the interim with facilitation and capacity building and play a role in transferring that capacity to the new city employee who would facilitate in the future.

Discovery

When stepping into that “guest” role, the Canopy often engages in a process of discovery, deep listening, and curiosity. After a “re-launch” meeting for the commission in May 2023, I started to see some things come to the surface.

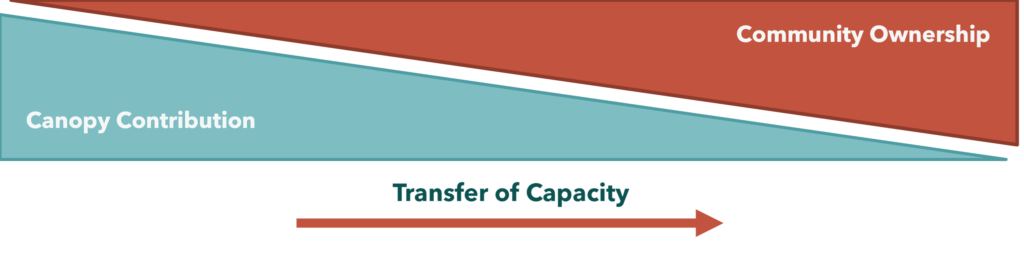

Though the group had made some progress in starting to round up resources and had created a list of agencies working on housing and homelessness, some people expressed some frustration around not knowing what others are working on, and what resources are available, and felt stuck in the silos of individual organizations. Within the commission itself, the roles were unclear; there were “official commission members,” but folks weren’t sure who the officially appointed members were. The meetings were also open to the public and partners who were not appointed. This led to confusion, and the group felt like members had great ideas but couldn’t make decisions on them to act together.

To go a bit deeper, I conducted 10 one-on-one discovery interviews and conducted an assessment based on our Community Learning Model with 19 responses and then shared back the data with the group to reflect on together. Through that process, we came to see that some folks were content with how the working groups had been able to act in certain areas, while others had seen a loss of momentum. Many folks told a shared story of the beginning of the commission being bolstered by the clear, unifying goal around building an overnight shelter, a huge gap in meeting the needs of unhoused neighbors. Once that shelter was up and running, it was less clear what the group wanted to collaborate towards. In exploring the way the commission operated, there were differences between what was on paper (in the bylaws and the general practices of city commissions) and what commission members were hoping for in this collaborative space.

Shifting Paradigms

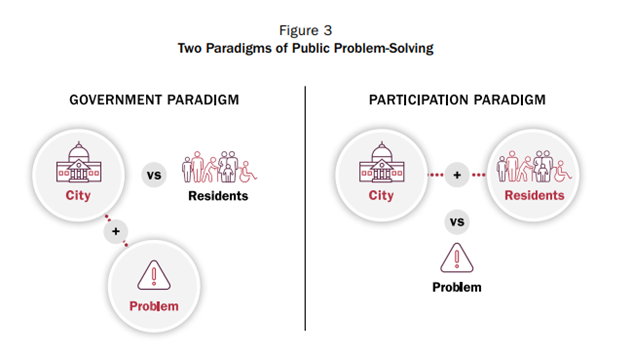

I will never forget the moment that I put up a visual from the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative, and the Pueblo Police Chief, Dustin Taylor, exclaimed “I know what that is!” He, along with several members of the City of Pueblo’s staff, had attended a training at Harvard that seeks to equip mayors and senior city officials to tackle complex challenges in their cities and improve the quality of life of their residents. So Chief Taylor explained this shift in paradigm to the commission. In the City Leaders’ Guide on Civic Engagement, authors explain the pitfalls city governments fall into:

While there are some technical problems that city government may be well equipped to address without extensive engagement, there are precious few public problems that city government can solve all on its own. The conventional government paradigm, in which cities set and enforce policy with limited public input, tends to pit city against residents, us vs. them. Residents complain about the quality of the services their governments provide or resent the burdens they impose; they refuse to comply; they protest existing policy and resist change. City officials are indifferent, bureaucratic, and inflexible; they have no understanding of residents’ experiences, expertise, and needs. Or so the usual story goes. An orientation to public problem-solving that centers city government as the decision-maker and positions residents as obstacles rather than thought partners and coproducers leads to poorly designed engagements. Interacting with citizens as collaborators rather than adversaries can lead to more mutually satisfying and productive engagement. (p.9)

The opportunity that this group had was to break out of that paradigm—to partner not only with residents, but community partners, service providers, volunteers, faith leaders, and people who are directly impacted by homelessness and access to affordable housing. Some of the key steps to support this shift would be to:

- Develop a Strategic Direction – at a half-day retreat in August 2023, the commission developed a refreshed strategic plan centered around three population-level results (the desired future for Pueblo):

- Housing – Pueblo has sufficient sustainable housing stock.

- Neighbors in Need – Pueblo’s neighbors at risk of becoming unhoused, currently unhoused, and transitioning into housing have their needs met.

- Shift the Narrative – Mental models around housing and homelessness in Pueblo center dignity, humanity, and community.

- Clarify the Structure – the group worked to clarify the roles of participants and created a steering committee that could support the facilitator to provide strategic direction to the commission.

- Move Towards Collective Decision-making – one of the group’s strengths is the diversity of perspectives and backgrounds of its members. The group was willing to experiment with decision-making which allowed the group to come to solutions that everyone could get behind with a certain tolerance for disagreement. This provides an opportunity to disrupt the often-polarizing climate that can lead to inaction or contentious decisions within city government.

But what is a paradigm shift anyway? Originally coined in Thomas Samuel Kuhn’s 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a paradigm shift is “an important change that happens when the usual way of thinking about or doing something is replaced by a new and different way.”

So, though this new way of thinking doesn’t quite come close to Copernicus putting the sun at the center of our universe or the invention of the internet… it will still certainly take some time to take root.

Taking Root

As all these changes were occurring, the city’s Housing and Citizen Services Department had finally hired the new facilitator, another Alexis (endearingly known as “Lexi #2”), Alexis Romero Stewart. For a few months, Lexi and I planned meetings together and co-facilitated meetings. Many moving pieces were coming to fruition: editing bylaws, creating new working groups, identifying measures of success, and continuing to seek buy-in and participation from partners and city and county stakeholders. As Lexi began taking on more of the responsibilities of planning, coordinating, designing, communicating with partners, and facilitating meetings, Pueblo’s larger context was also shifting. Some elected officials still seemed unclear that there was a collaborative group working on the issue; there was a persistent perception that ‘nothing was happening.’ It was also challenging to ask partners who are already stretched for capacity trying to maintain their programs and services to collectively take ownership of a collaborative group (rather than relying solely on the facilitator).

A run-off election in January 2024 led to Heather Graham being sworn in as the second mayor since the city moved away from a city-manager-run government. Homelessness continues to be a hot-button issue played out on the public stage, including the passing of an ordinance to criminalize camping on city property that could result in a $1,000 fine. In response to the hours of public comment both in favor of and opposing the ordinance, Mayor Graham held a round table discussion where she expressed, “I’m looking for sustainability and long-term solutions.”

The Canopy team played one small part in this unfolding story around a collaborative effort in Pueblo. We helped to weave the thread from one piece of the tapestry to the next, ultimately putting it back in the hands of the community.

Reflecting on the journey the commission went on, Lexi Stewart, the current facilitator of the group, shared:

“The work The Canopy did to help support and re-establish the group in a pivotal time was instrumental in not only keeping the group alive but also re-invigorated its members to the point where they were prepared and excited to re-engage and start working on new initiatives. I feel if you hadn’t stepped in and led that charge, I’m not confident the group would have had the motivation to continue their work.”

There is far more work ahead for this Community Commission on Housing and Homelessness. They are tasked with not only working towards a vision of access and opportunity to suitable, safe, and affordable housing but also finding a way towards that vision that creates space for collaboration, especially when people disagree on how to get there. To create a community where everyone has what they need to not only survive but thrive, it’s safe to say that they may need to shift the paradigm—and do things a bit differently.