“The System is Broken”

In a time when the political left and the political right can’t agree on even basic facts, they do agree on one thing: “The system is broken.” People might mean different things by that statement and have different reasons for saying it. But beneath those differences is a common sentiment that today’s challenges stem from deeper patterns and structures that are fundamentally flawed.

While common ground feels like good news in a polarized world, it unfortunately shows a loss of trust in the institutions and processes we need to fix those problems. At the Civic Canopy, we’ve been working on systems change for a while, but something’s been missing. Where’s the “I” in the system? How do our beliefs about systems, and our relationships with each other, affect how we make change happen? We are excited about some tools and models that are helping us evolve our thinking about these questions.

Background and Past Work

The Canopy team has been working with concepts related to systems change for much of the past 10 years, kicked off in large part by the publication of two key articles by Peter Senge and the team at FSG: The Dawn of Systems Leadership and The Water of Systems Change. Both articles draw heavily from Senge’s decades-long work in systems thinking but with a new focus on the collaborative community work inspired by the broad interest in collective impact. Like the authors, the Canopy team encountered the practical need to think beyond programs and organizational collaboration to begin shifting the systems that hold problems in place.

The Canopy has found value in the “Six Conditions of Systems Change” framework put forth in these articles. This “inverted iceberg” model has helped highlight the different aspects of systems change, from the explicit and easily visible examples of changing policy, practices, and resource flows, down to the implicit levels of shifting mental models. These concepts connect easily with our work around narrative change as well. The model also formed the foundation for designing Level Up!, a game designed to help people better understand what the concepts of systems change could look like in action.

While these articles and concepts have been most central, the Canopy’s work and thinking has also been heavily influenced by other sources as well, including adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy, David Peter Stroh’s Systems Thinking for Social Change, Emergent Learning from Fourth Quadrant Partners, and numerous other sources that draw from natural systems thinking to help make sense of how to change human systems as well. The Canopy has also learned a great deal from partnering with the Tamarack Institute, especially Liz Weaver and Mark Cabaj, drawing upon their decades-long work in facilitating and evaluating systems change.

A Next Exploration in Understanding Systems Change

As the Canopy took the important turn down the road of “leadership disruption” in 2021, and into “leadership emergence” and eventually on to formulating The Canopy Way in 2023, the focus of our systems change work shifted from training about it with external partners to experiencing the power of it internally as an organization. A core resource for this journey was Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations which captures the stories of dozens of organizations across the globe who were trying to invent the next version of an organizational structure. One that moves beyond dominating hierarchies and into a form consistent with the principles of how healthy systems function.

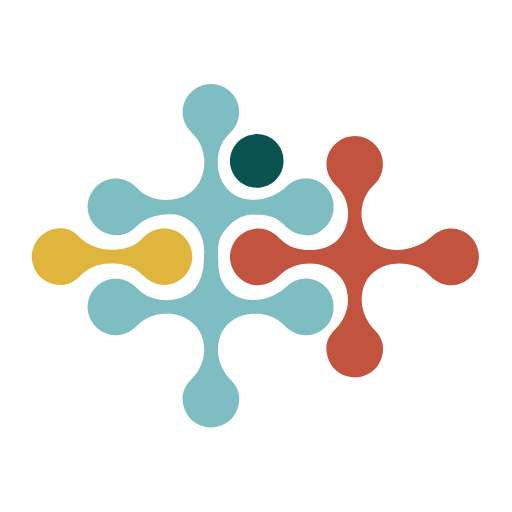

Embedded into Laloux’s framework is a powerful synthesis of human development outlined by philosopher Ken Wilber in his integral theory that suggests that evolution can be understood through “levels” and “quadrants.” First, the human species’ evolution through history mirrors the development of the individual person over a lifetime—more on these “levels” below. Second, the model highlights the fact that everything has an interior dimension and an exterior dimension, and is either individual (singular) or collective (plural). And that all of these dimensions, or quadrants, are co-evolutionary, and mutually influencing each other. So the upper left quadrant—Q1 or what Wilber calls “intentional”—is comprised of our thoughts, emotions, mental models, and states of mind. This quadrant is a direct product of Q2—the individual exterior dimension of our body and our brain (“behavioral), which is further influenced by our social systems and structures (Q4, “social”) in the world around us, which of course flow from the cultural norms, value systems, and relationships we are immersed in (Q3, “cultural”).

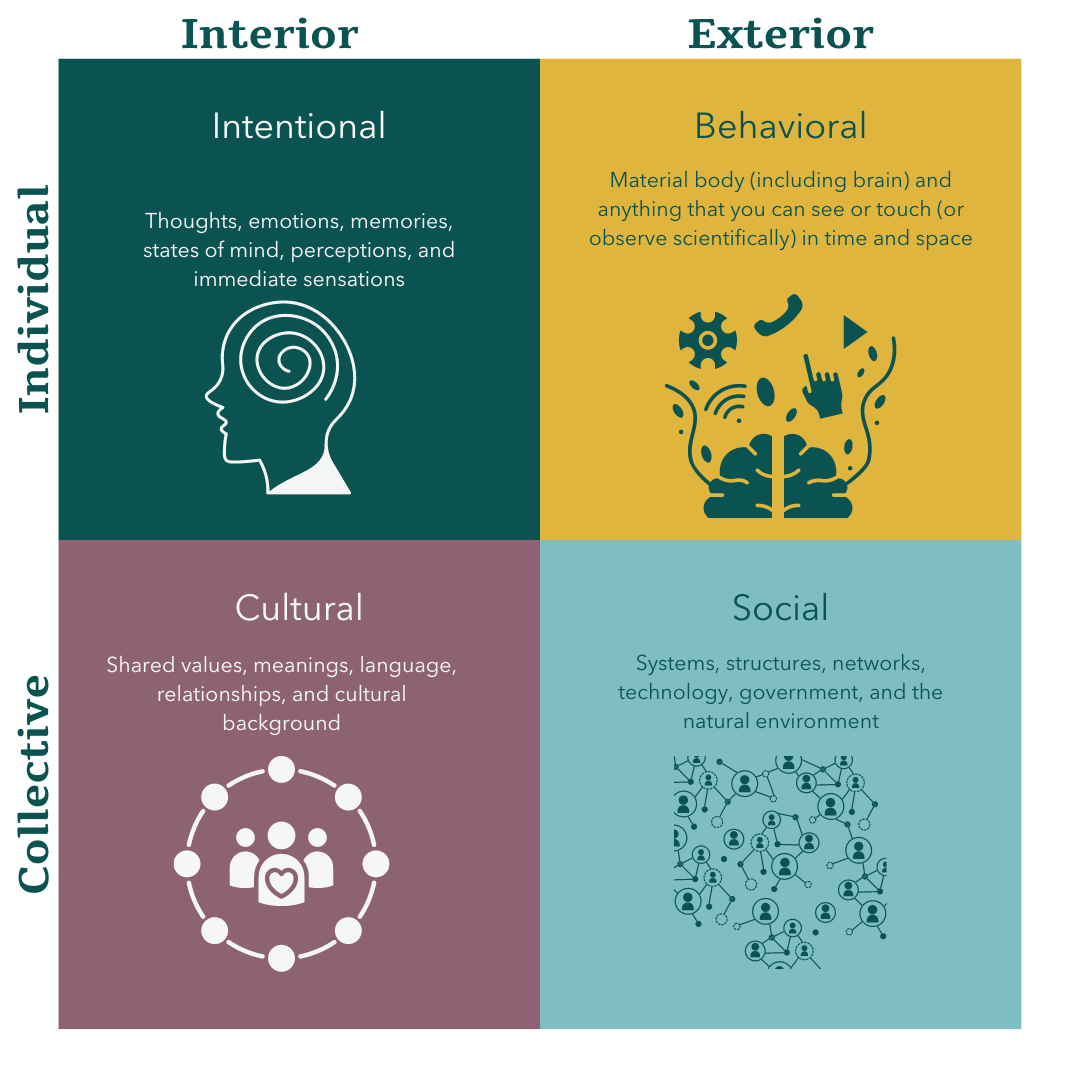

To illustrate how this plays out in real life, consider the example of understanding a common challenge of our age: the steep rise of teen suicide. One can try to analyze this issue through any of the four quadrants alone, but it is far more powerful to see their interplay. For instance, some might wonder if it has been caused by a change in teens’ mindsets and mental models—Q1. This would involve understanding the experiences of individual teens, the pressures they might feel, the hopes and fears that run through their minds, and the mental models they hold about how the world is supposed to be and their place in it. The knowledge gained from this inquiry is made more valuable by understanding the changes in the body and brain (Q2) that occur during adolescence. Combining these insights is useful but adding the influence of the internet and the rise of the iPhone (Q4) is essential to a true understanding of the issue. Of course, one cannot truly understand the full picture without the cultural influence of social media and the rise of cyberbullying (Q3). None of these stories alone is as powerful as seeing how they all interact, with each one having an impact on the others to co-create a culture of rising angst—and in some cases resistance—spurred on by the ubiquitous use of cell phones, social media, and a culture that is “very online.”

this issue through any of the four quadrants alone, but it is far more powerful to see their interplay. For instance, some might wonder if it has been caused by a change in teens’ mindsets and mental models—Q1. This would involve understanding the experiences of individual teens, the pressures they might feel, the hopes and fears that run through their minds, and the mental models they hold about how the world is supposed to be and their place in it. The knowledge gained from this inquiry is made more valuable by understanding the changes in the body and brain (Q2) that occur during adolescence. Combining these insights is useful but adding the influence of the internet and the rise of the iPhone (Q4) is essential to a true understanding of the issue. Of course, one cannot truly understand the full picture without the cultural influence of social media and the rise of cyberbullying (Q3). None of these stories alone is as powerful as seeing how they all interact, with each one having an impact on the others to co-create a culture of rising angst—and in some cases resistance—spurred on by the ubiquitous use of cell phones, social media, and a culture that is “very online.”

Leveling Up Through Time

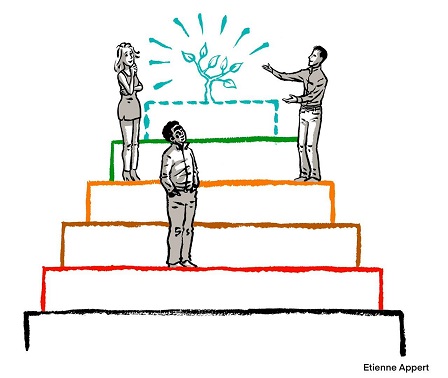

The interplay of all four quadrants—and the fact that our historical social structures (from hunter-gatherers, to agrarian, to industrial) have shaped our mental models and vice versa—sets the backdrop for understanding much about. Laloux borrows Wilbers color scheme to mark breakthroughs in human evolution caused when the previous worldview and social structure came into conflict with the complexities of the time.

The stage of human development that corresponded to hunter-gatherers and clans—the Red stage—was characterized by simple, nomadic social structures, no formalized laws or codes, and a reliance on sheer power as a main operating system. This served humans well for hundreds of thousands of years, and the rule that “might makes right” worked—until it didn’t.

Starting around 4,000 BC, we see the emergence of the next stage—Amber—characterized by formal laws and codes, an agricultural social structure that gave rise to empires and larger bureaucracies. This period gave birth to most of the world’s major religions and spiritual traditions, written languages, as well as powerful social mores and cultural forces like guilt, shame, and loyalty.

The stability of the Amber period was upended by the rise of the scientific revolution in the Enlightenment and growing confidence in control over the world around us through top-down organizational systems, the expansion of capitalism, colonialism, and industrialism, and a new model of “universe as a machine.”

This paradigm dominated the globe until the middle of the 20th Century when the Green worldview resisted the materialistic obsession and controlling models of hierarchy to posit a counterculture of inclusion and values-driven change. Social movements focused on women’s rights, civil rights, and concern for the environment challenged the central focus on productivity, exploitation, and control ushered in by the Orange worldview. And while the Green worldview is still ascendant, the signs of a shift to Teal consciousness are emerging, characterized by self-organizing systems, the rise of network structures, and a decentering of the individual ego.

This is an oversimplification of human evolution to be sure, and open to many critiques. It can convey a sense that evolution is always progress, that progress is inevitable and linear, and that anything newer is always better. None of those are the case. But in the spirit of “all models are wrong, but some are useful,” the basic story of each stage introducing both new solutions and new challenges highlights the parallels between our collective evolution and our individual development. Both stem from the fundamental challenge of addressing complexity—and the need to adapt our individual and collective responses to change. Seeing within these stages of history an analog in the individual lifespan—with our “Red” years of terrible twos on up to adult stages of Orange efficiency and Green/Teal striving for inclusion and justice—offers a way to think about our unique stage in history through a useful lens.

So What? Changing Systems in the Real World

So let’s put the two pieces together—the four quadrants, and the notion of moving up through levels of evolution in consciousness. Suppose the age we are living in is characterized by the emergence of a Teal consciousness that “transcends and includes” the previous levels of Green, Orange, Amber and Red. In that case, we can imagine a new way of addressing the perennial challenges generated by the previous paradigms. These paradigms of control, efficiency, and productivity that made possible enormous advances in health, medicine, transportation, and material production, but which has wreaked havoc on the environment, social ties, and traditional ways of organizing society.

Using the Civic Canopy’s example of transformation, we see that it was necessary to upend the traditional organizational structure of a top-down org chart to unleash a culture of shared power and mutual accountability. And in shifting both that structure and the culture, we’ve seen a corresponding increase in engagement and sense of responsibility, reflected in marked increases on annual team engagement surveys among other measures. It would not have been possible to generate that kind of individual self-empowerment without factoring in a shift in our structures, policies, and power-sharing (Q4), and that shift would not have been possible with an intentional raising of individual consciousness to believe it was possible and important (Q1).

Applying this model to a larger scale, we can see systems changing around the state as well. As outlined in a recent case study, we are seeing the emergence of a new kind of structure across the state—a network of networks that is capable of collaboration at scale to shift the way important systems function in Colorado. The Colorado Outdoor Partnership supported by Color ado Parks and Wildlife consists of 16 regional partnerships charged with coordinating the health and well-being of local environments while working within a larger statewide framework. Instead of different areas competing against each other for scarce resources and jeopardizing the vibrancy of the state’s ecology, the regional partnership acts as a learning network to scale innovation, address common concerns, and ensure that limited funding has the largest possible impact.

Tools of the Trade: How to Bring About Systems Change

While not an easy task, the art and science of promoting systems change through the perspective of this all-quadrant, all-levels approach is no different than we have been doing all along. The Community Learning Model is still the primary model of engagement, as it creates the conditions for generating commitment, aligning efforts, and mobilizing collective action. So, trying to help a group of people collaborate toward a shared goal when most of them are operating out of an Amber or Orange worldview is a very different task than working with individuals who have reached a Teal level of operating. It is thus imperative to meet people where they are and highlight the benefits and the limitations of the different worldviews to create space for people to engage on their terms and make sense of the challenge and opportunity in their way. We look forward to exploring this approach more deeply at our upcoming Summit—and hope to see you there.