Have you ever gone to fill out a grant report and found that the things that you said you would do three years ago feel like a different person wrote them? And yet, you know you did good work on the grant and great things came out of it…it just isn’t what you thought was going to happen. When we’re working on long-term, systemic change, the signals of progress are hardly linear. We recently worked on a project using Ripple Effects Mapping to solve a similar problem.

We were able to apply Ripple Effects Mapping in its work as an evaluator for the Sperry S. and Ella Graber Packard Fund for Pueblo (Packard Fund). The Packard Fund was established in June 2019 and has provided grants to programs and entities that support Children, youth, and families; or Community Impact in Pueblo. Using Ripple Effects Mapping, we sought to answer the question: What was the Packard Fund’s impact on Pueblo? Our project team was led by Bill Fulton and included Daniela Young, Gloria DeLoach, and Laura Kam.

Ripple Effects Mapping is an evaluation tool that identifies the greater outcomes of an intervention rather than stopping at its direct outcomes. Its purpose is to unearth cascading intentional and unintentional ripple effects. Each action we take is like a rock skipping across the water. It creates ripples, both intended and unintended. This evaluation method allows us to capture those ripples and see what they in turn caused. It arose between 2007 and 2009 with the convergence of the methods used for the Community Capitals Framework and Horizons Program evaluations (1). It combines the steps of one-on-one interviews, group discussions, mapping stories, and qualitative data analysis.

Starting off, we worked with the Packard Fund staff to determine the right stakeholders to participate in Ripple Effects Mapping. We decided to invite the grantees of the Packard Fund because they would be most knowledgeable about the direct impacts of the fund in Pueblo and the further ripple effects through their work. We also decided to have two sessions so that the number of participants in each session was not so large that it prevented participants from being able to speak, or too small to hinder making connections between stories that are shared. We invited 29 grantee organizations to participate. The sessions ultimately brought together 25 representatives of 23 grantee organizations.

At the Ripple Effects Mapping sessions, Bill and Daniela, the Canopy facilitators, introduced the process and invited the grantees to conduct paired interviews. This served the dual purpose of giving grantees enough time to share their stories and allowing grantees to connect. The paired interviews focused on the following questions:

- What is a highlight, achievement, or success you had based on your involvement with the Packard Fund? What did this achievement lead to?

- What new or deepened connections with others (individuals, community organizations, government, philanthropic) have you made as a result of these efforts? What did these connections lead to?

- What unexpected things have happened as a result of your involvement in these efforts?

Following the paired interviews, Bill and Daniela led the grantees through a group reflection where people shared their connections, and we transcribed them on sticky notes and an online Mind Map. Facilitators emphasized both capturing the many ways this effort has rippled out and on ensuring a rigorous look at causal connection. Follow-up questions helped to test the connections, such as:

- Would this outcome have happened if not for the Packard Fund?

- How much of that outcome can be attributed to the Packard Fund?

- Is there an alternate explanation that is more compelling?

As stakeholders shared their stories and ripple effects, we were mindful to note causal connections instead of just sequences in time. A good example would be: Grantee A received the grant, attended a leadership cohort, and from the cohort doors to a new funder opened. The conclusion from this would be that involvement with the Packard Fund opened new doors to other funding. A bad, non-causal example might be: Grantee B received a grant, then COVID hit – with the conclusion that the grant caused COVID. There needs to be a clear association to determine a ripple effect and no other plausible explanation that better explains the connection.

One grantee shared how the Packard Fund created a ripple that led to increased collaboration between nonprofits in Pueblo:

“I’ve had a lot of achievements (and) successes due to my involvement with Packard, but the Leadership cohort I took part in had the biggest long-term impact. I learned new skills to help me be successful as an Executive Director and made a new network of professional colleagues. I was connected to a lot more nonprofits due to the Leadership Cohort. This was a natural way for us to build trust and find ways to collaborate with each other. These connections have led to better outcomes for our community by being able to offer more services by working together.”

Another grantee shared how the Packard Fund created a ripple that contributed to the creation of the Mental Wellness Task Force for Southern Colorado:

“(Packard) Funding…. (brought) mental wellness services to youth – youth kickback groups, one on one therapy, youth mental wellness handbook for Southern Colorado. Funding has helped break down silos. Youth Kickback has upwards of 15 partners working together for suicide prevention with youth… Through Youth Kickback as well as the struggle youth and families have finding mental health services and crisis services – the Mental Wellness Task Force for Southern Colorado was created.”

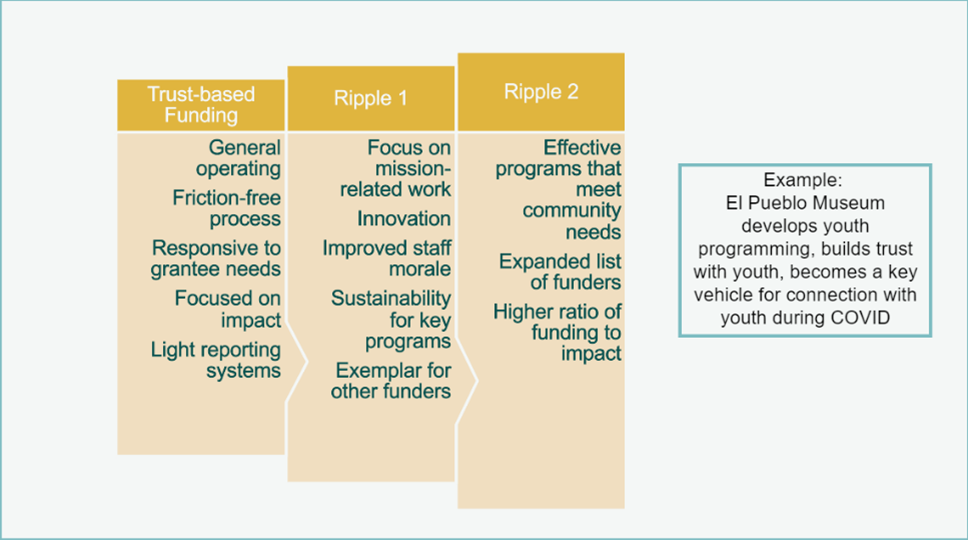

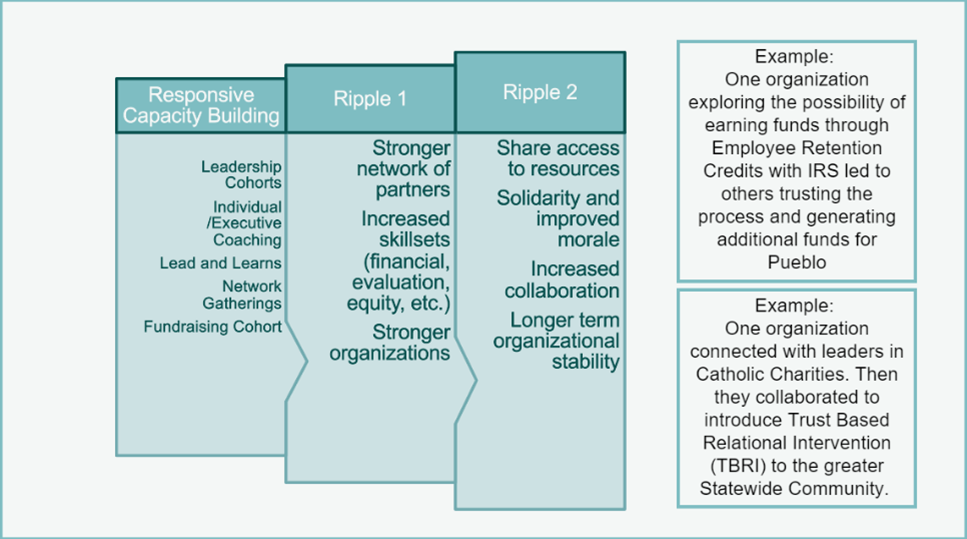

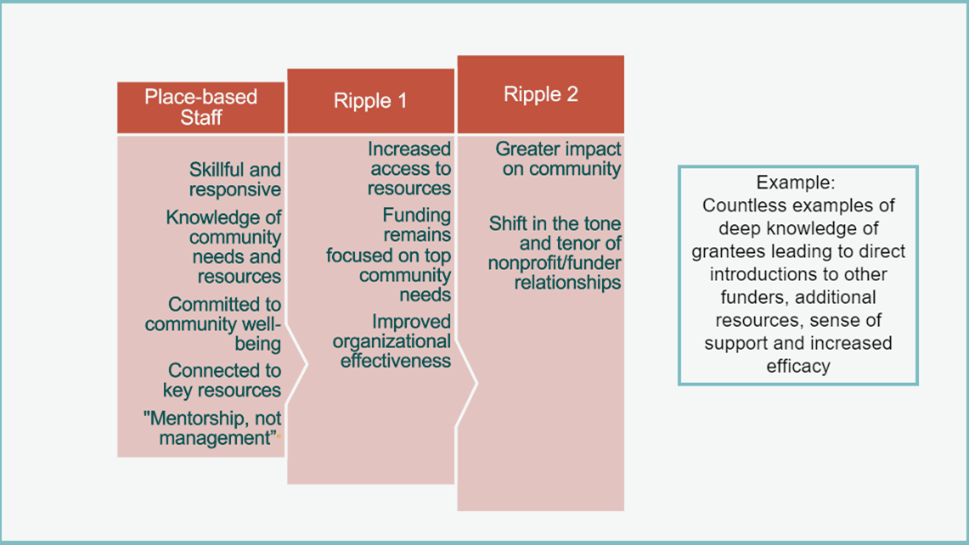

Next, the Canopy facilitators sought to identify what themes emerged based on the various stories that were shared, and how the examples in the stories could be connected together through ripples. Hearing each other’s stories, participants built upon them with further stories and connections. The top themes that emerged from the grantees’ stories were that the Packard Fund provided trust-based funding; responsive capacity building; and had place-based staff. These characteristics of the fund led to the creation of effective programs that met community needs, and nonprofits that shared access to resources and had greater organizational stability. Using the Ripple Effects Mapping process was an effective tool to demonstrate the holistic impact of the Packard Fund on Pueblo and highlight examples of greater nonprofit collaboration and stronger programs.

Some of the ripple effects and examples are captured in the images below:

Works Cited

Chazdon, Scott and Mary Emery, Debra Hansen, Lorie Higgins, and Rebecca Sero. A Field Guide to Ripple Effects Mapping. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2017.